| The Manifesto | | | The 8 Houses | | | Texts and Articles | | | Review | | | Links | | | ACCUEIL (FR) | | | HOME (EN) |

| Reconsidering the "Nostradamus Plot"

(New Evidence for the Critical Evaluation of the Chronology of the Editions of the 'Prophéties') by Dr. Elmar R. Gruber |

The discussion about the true publication dates for the quatrains of the Prophéties represents an important step in the critical analysis of the work of Nostradamus and its evaluation. It is a significant effort, not only for bibliographical reasons. Apart from the question whether - for whatever reason - particular quatrains have been introduced at a later stage by someone else other than Nostradamus himself, it is also essential for the assessment until which year the prophet of Salon could have incorporated contemporary events in the guise of prophecies, as is one of the general assumptions of many critical historical studies. The search for the true publication dates of the diverse editions of the Prophéties is indeed an essential basis for all critical appraisal of the prophetic work of Nostradamus. However much of the controversy about this issue unfortunately seems biased through preconceived ideas and favored hypotheses, one of which led to a real "Nostradamus plot", involving a large number of diverse, allegedly antedated works.

Prévost in search of Nostradamus as chronicler of the civil wars

One of the chief proponents of the view that all of the quatrains from the centuries have indeed appeared in print at the earliest very late in the life of their supposed author Nostradamus is Roger Prévost. [1] His premise is, to interpret a great number of quatrains from the Prophéties as reflecting historical events from the time of Nostradamus or prior to this epoch. Prévost concludes that Nostradamus was more or less a chronologist of the hardships of his time. For this reason he explains many quatrains as reflecting events during the religious civil wars which broke out in 1562, although we know of different editions of the Prophéties bearing publication dates prior to 1562. He takes for granted that the quatrains in question have been composed after these events took place.

Prévost does not go into detail about the true publication dates of the centuries, he basically presupposes, by using very general arguments that they did not appear before the realization of certain incidents, which he believes Nostradamus has narrated in his gloomy verses. Therefore Prévost puts forward the hypothesis that no quatrain from the Prophéties was published before the initial stages of the religious wars. As a proof for this assertion he claims that all the early published criticism of Nostradamus rests solely upon the almanacs and makes no mention whatsoever of the centuries. He asserts that there is no allusion to the centuries neither in Antoine Couillard's pamphlet of 1560 [2] , nor in the heavy attack of Laurens Videl of 1558. Moreover Prévost declares that in the pamphlets of the early critics we can neither find a reference to the letter to César, nor to the ominous year 3797 for the supposed end of his predictions. [3] Unfortunately he gives away much of the weight of his critical position with such poor and utterly wrong remarks. In the end it seems that he was only eager to save his hypothesis by making these statements. Prévost conceals the existence of another work by Couillard, Les prophéties du seigneur du Pavillon lez Lorriz, published already in 1556. In this oldest pamphlet against the prophet we encounter the surprising sarcastic passage:

"Non pas que j'entende & veille parler de perpetuelles vaticinations pour d'ici à l'an 3797. Car que diable me serviroit d'en parler si avant, puis que noz nouveaux prophetes nous menassent que le monde s'approche d'une anaragonicque revolution, & qu'il perira si tost: j'ay toutesfois bonne affection laisser par estat, avant la corporelle extinction, mes inscrutables secretz, non seulement pour servir à Martial mon filz, l'aage duquel ne te veux celer, comme nostre maistre Nostradamus grand philosophe & prophete, veult en son epistre tant espouventable taire les ans de Cesar son filz. Car le mien est aagé de quatre ans six moys dix jours trois heures trente minuttes & demie." [4]

This of course is a very detailed reflection of a section from the Épître à César, making reference to Nostradamus's mention of the "perpetuelles vaticinations, pour d'yci a l'an 3797" [César 33 [5] ]. The other remarkable citation by Couillard in this excerpt concerns the neologism invented by Nostradamus of the "anaragonique revolution" [44] and his allusion to the strange sentence at the beginning of the letter: "[...] & ne veulx dire tes ans qui ne sont encores accompaignés, mais tes moys Martiaulx [...]" [2].

These are just a few obvious examples of how well Couillard already knew in 1556 the letter to César, as we can find many more allusions to it in his booklet whenever he tried to deride the prophet. In addition, in Videl's attack of 1558 there are a number of unambiguous references to the Épître à César. To Nostradamus's explanation that he gets his inspiration "[...] non par bacchante fureur, ne par lymphatique mouvement" [5] Videl reacts with the words: "Luy [...] nous veut inventer une nouvelle astrologie, forgée en sa furye bacchanale & non limphatique (comme il dit), sur umbre de prophetie." [6] To the prophet's bold allegation "[...] non que je me vueille attribuer nomination ni effect prophetique, mais par revelée inspiration [...]" [32], Videl answers in anger: "O arrogance superbe & folle! tu ne te contantes de te vouloir faire estimer prophete ? ains veux estre plus que prophete? par revellée inspiration." [7]

And again we find an outraged Laurens Videl, mad about the claim of Nostradamus about having written perpetual prophecies which he had obscured by muddling them up in disorder and by doing so declaring himself superior to the great prophets from the Old Testament: "Tu, donc, Michel, as composé (comme tu dis) livres de propheties ? & les as rabotez obscurement, & sont perpetuelles vaticinations ? Jamais Moise, David, Isaie, Jeremie, Daniel, ny les autres ne se vantèrent d'un tel fait, d'avoir composé vaticinations perpetuelles, ainsi que tu fais." [8] We likewise encounter in Videl's work a reference to the year 3797, which Prévost would not find mentioned in any of the early critics: "O grand abuseur de peuple! Tu dis que tu as faict de perpetuelles vaticinations, & après tu dis qu'elles sont pour d'icy à l'an 3797. Qui t'a assuré que le monde doyve tant durer ? N'est tu pas un assuré menteur ? Car les anges mesmes n'en scavent rien." [9]

Another important argument in favor of the existence of a version of Les Prophéties by Nostradamus in 1555 is the very title of Couillard's pamphlet of 1556 Les Prophéties du Seigneur du Pavillon Lez Lorriz, which obviously was articulated in these words as an ironic copy of the work it denounces. As Robert Benazra has recently pointed out, besides the title, the work of Couillard is divided into four books, "comme pour faire écho aux quatre centuries de l'édition Macé Bonhomme". [10] In regard to the works of Nostradmus he is attacking, Couillard speaks of "nouvelles prophéties & prognostications", which seems to indicate that he distinguished between the yearly prognostications and Les Prophéties. Benazra draws our attention to a most important statement of Couillard, who affirms that the author he is deriding has composed with marvelous labor "trois ou quatre cens carmes de diverses ténébrositez" (fol. E2v). This beyond any doubt is an allusion to the 353 quatrains of Les Prophéties published by Mace Bonhomme in 1555, which Couillard describes on different occasions as "fantasticques compositions" (fol. A4v et D3v) and "carmes tenebreux et obscurs" (fol. B1r).

Interestingly enough there are a number of expressions in Couillard's pamphlets which we find in Nostradamus's epistle to Henry II. Moreover Couillard cites a number of sections from Roussat's Livre de l'estat et mutation des temps which Nostradamus copies almost exactly in this same letter to Henry II. Hence, Benazra suggests, he may have used the pamphlets of his adversary for formulating his own text. [11]

For Prévost this is a serious blow to his allegations and might jeopardize his main argument. It is very probable, if not almost certain that a number of quatrains were definitely published before the events took place, which they supposedly describe in Prévost's accounts and presented by him with great authority. This would mean that he himself, who does not believe in the prophetic faculties of Nostradamus (or anyone, for that matter), offered the best arguments in favor of their existence. In reality this procedure shows that scholarly interpretations of Prévost's type, at times suffer the same fate as the explanations found by uncritical "nostradamians", if they are based on preconceived ideas. [12] In any case, judging from the above cited passages from the early critics, it would seem beyond any doubt that the first part of the centuries which carries the Épître à César was indeed published by 1555.

A refined and much more erudite line of reasoning in this respect has been put forward by Jacques Halbronn. His approach is basically the same as Prévost's, considering all prophetic texts of Nostradamus' or the ones attributed to him, more or less as either past events merged with power of imagination in the guise of future occurrences or politically motivated propaganda statements. Halbronn is a fervent defender of the idea that all the known early publications of the Prophéties are antedated products of a much later time. As a serious scholar of the matter, in contrast to Prévost, he acknowledges the existence of detailed early criticism of the contents of the Épître à César. But in order to save his thesis, Halbronn has to postulate an initial separate publication of this letter to his son César. [13]

Apart from the fact that there is no evidence whatsoever that the letter was ever published on its own, the question remains, why should this epistle have been printed separately? It is obvious from the content that it was composed as an introduction to a prophetic text and consequently it is termed "Preface de M. Michel Nostradamus à ses Propheties" since the Bonhomme 1555 edition. Why should the letter alone, without the proclaimed prophecies, have incited such harsh criticism from Couillard and especially from Videl? It is true that in it Nostradamus makes some outrageous declarations about his prophetic faculties, surpassing the licit domain of an astrologer, and hence the criticism centers on exactly these claims. But without the "perpetuelles vaticinations" [33] announced in the letter, it is hardly conceivable why furious critics would go to the trouble of publishing their condemnations, if the author had still to prove that he would put out the prophecies announced. In my opinion it was exactly the publication of the first part of the centuries, as they appear in the 1555 Macé Bonhomme edition that generated this type of disapproval. As it was obviously of no value to attack the quatrains themselves, since their meaning was simply not understood by the opponents or because they were meant to describe events in some distant future and their coming into being could neither be confirmed nor rejected, they attacked the excessive claims of prophetic powers that the author ascribed to himself in the Épître à César.

Interference of the League in the formation of the Centuries?

One of the dearest arguments of Halbronn is the political instrumentalization of prophetic texts in general and of Nostradamus's works in particular. There is no doubt that prophetic writings have suffered this fate to a substantial degree, [14] and we know that the oeuvre of Nostradamus makes no exception. Indeed the "prophetic tradition" [15] is basically the product of a continuous interference with and alteration of the literary and oral transmission of prophecies. Hence it is a legitimate and important question to determine which texts were written by Nostradamus and when they appeared for the first time in print. This is an especially difficult task, because of the large number of editions of his main prophetic work Les Prophéties, the scarce availability of his almanacs and prognostications, as well as the considerable number of forgeries and counterfeit productions.

In various publications Jacques Halbronn put forward the thesis that a group of quatrains shows unambiguous political positions and propaganda from the time of the League in the years between 1588 and 1595. [16] He argues that these quatrains had been written by the Catholic party and were aimed against the Huguenots. Halbronn points to the fact that the edition of the Prophéties by Raphäel du Petit Val at Rouen in the year 1588 contains the first three centuries completely and 49 quatrains of the fourth centurie. It lacks quatrains 44 to 47 of the fourth centurie. He asks how it is possible that such a fragmentary version could be published 33 years after the supposed first edition by Macé Bonhomme in Lyon 1555, which already contained 53 quatrains of the fourth centurie. Since the four absent quatrains can be found in editions of 1590, e.g. in one from Antwerp, Halbronn concludes, that the fourth centurie did not contain 53 quatrains in 1588 and that four of them were inserted in the following months. This, he believes, may be determined from the contents of the missing 16 verses, which to his opinion were directed against the partisans of the protestants and of the duke of Navarra.

But Halbronn still needes to produce convincing evidence for the presumed polemic contents. His line of reasoning rests solely on the single verse "Garde toy, Tours, de ta proche ruine!" (C 4.46.2). [17] Tours was on the side of Henry of Navarra and the followers of the League had presumably added this and the other quatrains, to attack the Huguenots. To an unbiased mind this seems a rather insubstantial reasoning, if one looks at the rest of the quatrain, in which London, Nantes, and Reims are mentioned in an association hard to unravel. Halbronn does not bother to analyze the remaining three verses of C 4.46, nor the other missing quatrains supposedly inserted by the Catholic propaganda. With good reason, since nothing can be found in them which would sustain his hypothesis. Neither C 4.44, written in occitan language, nor the other two quatrains have the slightest bearing on propaganda-issues connected with the League.

It is obvious that Halbronn recognized in "Garde toy Tours" something that I termed a signal expression, [18] of the kind known from the nostradamians, who pick out such phrases, seemingly standing out and denoting - beyond any doubt in the mind of the interpreters - a certain "predicted" event. Around these signal expressions they construct their audacious and deranged exegeses. Here we encounter the instrumentalization of a signal expression for supporting a preconceived critical hypothesis. Around these words Halbronn weaves his thesis of the appropriation of the nostradamic prophecy by the League. He also identifies in other centuries, especially in the seventh and in the last three, the penmanship of the League. His conclusion: All known publications of the Prophéties before 1588 are antedated. Halbronn concedes at least that there might have existed unknown editions from the years 1555, 1557 and 1560, but those still extant today bearing these publication-dates, allegedly contain quatrains composed during the time of the League and must therefore be regarded as antedated.

Of course Halbronn is right in pointing to the many inconsistencies concerning the publication history of the Prophéties, and falsifications and antedated editions are indeed known. But here it seems obvious that a conclusion is forced in order to underpin a favored hypothesis. If the adherents of the League were in possession of fragments of the Prophéties, to which they added propaganda material of their own, and disseminated them subsequently among the people in antedated issues, one has to pose the question why they should have done it in such a useless way. Before Jacques Halbronn produced his study, no one had ever recognized the handwriting of the League in the specific quatrains. What value has propaganda, if its meaning cannot be communicated? Propaganda would only unfold its efficacy, if the intended general idea could be transported to the readers. Only in this way, modifications and insertions in prophetic texts have worked through the ages and formed the particular trait of the prophetic tradition. The quatrains inserted during the time of the Fronde against Mazarin were recognized immediately in their allusions, because their intentions were obvious. But the meaning of the quatrains presumably written as propaganda texts by the League as promoting the Catholic cause, is not at all clear. The supposed correlation to the League is only the result of the particular perspective of a scholar and his thesis. No reader would have come to the same conclusion. What effect would an advertisement have, whose message would remain unnoticed? Patrice Guinard correctly points to this fact and shows that the verse "Garde toi Tours de ta proche ruine" could well have been written as a contemporary reaction to social tensions due to religious discord et the end of the 1550s. [19] Or the whole group of missing quatrains 44 to 47 from the fourth centurie, including C 4.46, could be placed, as Roger Prévost has done, into the years 1560 and 1561.

If indeed the insertions were the work of Catholic propagandists and ended up in antedated versions, like the 1555 Macé Bonhomme edition, why would they not have omitted other quatrains, which were definitely working heavily and openly against the Catholic position, like C 1.52 and C 2.97, to mention just two? In the latter we find the same type of warning as in C 4.46.2, but this time aimed against the pope:

C 2.97

Romain Pontife garde de t'approcher

De la cité qui deux fleuves arrose :

Ton sang viendras au pres de là cracher,

Toy & les tiens quand fleurira la rose.Evidently, if propaganda intentions played a part in producing such antedated editions, the falsifiers had no idea of propaganda by retaining such quatrains. Another example is of course C 1.52 with the terrifying third verse (from the viewpoint of the Catholic Church).

C 1.52

Les deux malins de Scorpion conjoints,

Le grand seigneur meurtri dedans sa salle :

Peste à l'eglise : par le nouveau roy joint,

L'Europe basse & Septentrionale.Consequently the ardent Catholic Jean-Aimé de Chavigny in his Janus François[20] had mutilated the third verse containing a phrase that could be read almost like a curse on the church and replaced the upsetting words by an asterisk:

C 1.52

Les deux malins de Scorpion conioints,

Le grand Seigneur murtri dedans sa sale.

* le nouueau Roy ioint

L'Europe basse & Septentrionale.Another weakness of this approach is the fact that Halbronn has no problem in putting aside the known editions of 1555, 1557 and 1568 as antedated, but underpins this very conviction by relying on editions from 1588 to 1589, or on the works of Antoine Crespin from 1570 onwards. He does not doubt that all of these books were published in these very years. What gives him the security to stigmatize the first group of editions as antedated and the latter as correctly dated? What if these works were themselves antedated and actually pertaining to even a later time of publication? If there are so many counterfeit and antedated editions, it would not seem improbable that the printings of 1588 and 1589 would be themselves part of this gigantic game of fabricating prophecies in the name of Nostradamus and the bubble of the beautiful hypothesis would burst as quickly as it was inflated.

One more fact that Halbronn does not explain is the following: If the known early editions of the Prophéties were really antedated in order to serve propagandistic purposes as he describes them, why did the forgers only falsify the date of publication and not the place of publication as well? It would make a much stronger cause for a pamphlet with a propaganda aim, to appear to have been published in a city against which its intention was directed, instead of being issued at a place known to belong to their own party. In this regard the propaganda making use of Nostradamus during World War II was doing a much better job. Der Seher von Salon, a publication of the Nazi propaganda machine, was published at a certain "Europa-Verlag" based in "London, Berlin, Paris". Forged interpretations of the centuries thrown from aircraft as the German troops entered France at Sedan carried feigned places of publication. In them the predictions of Nostradamus supposedly announced that the south-east of France would be spared during the war. They therefore apparently worked. Part of the civil population fled in this direction, as Walter Schellenberg, director of the foreign intelligence office at the Reichssicherheitshauptamt and one of the leading staff in the entourage of Himmler, notes in his memoirs. As a consequence the streets were emptied for the advance of the German troops towards Paris. [21] A study by Karl Ernst Krafft commissioned by the Nazi department of propaganda as part of psychological warfare, published under the title Comment Nostradamus a-t-il entrevu l'Avenir de l'Europe, was supposedly published in Brussels.

The British intelligence departments tried a counter-attack using the same means. Louis de Wohl forged issues of the German astrological periodical Zenit which were subsequently smuggled into Germany. [22] He advised British intelligence departments in the publication of a booklet entitled Nostradamus prophezeit den Kriegsverlauf (Nostradamus Predicts the Development of the War) which carried the feigned German printer Regulus-Verlag at Görlitz, who specialized in occult and astrological books. In it he changed the first word "celuy" of C 3.30 to "Hister" and translated it in the sense that Hitler will be killed by six men in the night.

Now, this is an application of nostradamic prophecy for propaganda means that would work. Halbronn cites only the edition of Cahors 1590 as an anomaly in this respect. He cannot conceive how this edition containing quatrains announcing the victory of the Bourbon over the Guise "pouvait raisonablement paraître à Cahors en 1590 alors que pour encore quelques années la ville appartient au réseau de la Ligue." [23] If it were a fake in the aim of political misinformation, it is exactly this fact that would make a more convincing case, since it would allegedly be published in the city of the enemy! But it is rather evident that there is no need to force such an explanation, neither for this edition, nor for the editions ascribed to forgers close to the League by Halbronn...

Halbronn's hypothesis - no doubt put forward with great eloquence and learning - is nonetheless based on rather flimsy evidence. Hence the judgement of Guinard [24] is perfectly sound that Halbronn has launched an elaborate hypothesis of a veritable gang of counterfeiters at the time of the League, which went unnoticed by contemporary and later authors. Moreover the contents of their supposed forgeries also went unnoticed and were therefore completely useless as propaganda.

I am convinced that all the inconsistencies surrounding the manipulations in the corpus of nostradamic prophetic verses that I have pointed out above, are not due to the fact that the editions in questions were antedated by followers of the League and that we have to look for alternative explanations of the peculiar publication-history of the Prophéties, which of course is far from being solved.

On the years of publication of forged almanacs and prognostications

Let us turn to the question of the centuries 5 to 7 and the end of centurie 4. In Halbronn's reconstruction of the chronology of the possibly true publication-dates of the centuries, [25] he places this group of quatrains among the latest to appear in print, in the 1580s. He concludes from the fact that Antoine Crespin in his compilation of the centuries from 1572 does not mention one single verse from the centuries 5 to 7 that these centuries did simply not exist during Nostradamus's lifetime. The absence of quatrains from this group at one single author is enough evidence for him. In an anonymous almanac of 1581 citing quatrain 78 of centurie 4 Halbronn found "la première attestation connue pour des quatrains appartenant à un groupe de centuries ignoré de Crespin, à savoir la seconde moitié de la centurie IV, les centuries V, VI et VII." [26] Again he is convinced that centuries 5-7 and the end of centurie 4 were produced by the League and inspired the counterfeit antedated editions of 1557. [27] This is manifestly wrong, as I am now able to show.

There is no discussion among scholars about the publication dates of the almanacs and prognostications of Nostradamus, since it makes no sense to antedate this kind of literature, except if a publisher would like to produce unsaleable dead stock. These booklets were meant to be out prior to the year their predictions were aiming at. The same applies to the counterfeit almanacs. It would only make sense to publish these at the right time. If they were antedated, no one would take notice of a product, which is already outdated, because it "predicts" events of a year by now in the past. We know that almanacs and prognostications were the best-selling publications of the time and produced in huge quantities. Yet today almanacs of that period are among the hardest books to find, and when the small booklets with few pages do come to auction, they are sold for enormous amounts of money. The reason is that they became obsolete once the year for which they were meant was over. The almanacs were thrown away and the next ones were bought. This is the reason why even Chavigny, only a few years after the death of Nostradamus, did not succeed in collecting a full set of all the almanacs of his master for his Recueil.

I have to go into detail about this issue, because Halbronn, oddly enough, is also prepared to include fake almanacs and prognostications among the heap of antedated works under the "Nostradamus plot". He does so, for example, in respect to the Significations de l'Eclipse of 1559 [28] , which he thinks was indeed written after the death of Nostradamus. Why would an impostor include in it the intention of Nostradamus of publishing a future apology with a detailed response to his opponents, when at that time it must have been known that he had never written such an apology? At the beginning of the section in which he attacks his critics, Nostradamus writes in the Significations: "Icy n'y à lieu de faire l'Apologie, dans laquelle toy & adherans serez vn peu plus amplement chapitrez, contentez vous pour le present de cecy." [29] This sounds much more like the genuine angry reaction of a man condemned in what in his eyes was an unfair way by unqualified individuals. Probably it soon seemed useless to him to answer all the increasing malice and harassment, and he abandoned the idea of the apology. [30] Halbronn tries to corroborate his position that the Significations is a counterfeit production, because in its first part it is basically a translation of a work by Leovitius on eclipses, [31] as already indicated by Torné-Chavigny.

For Halbronn "le recours à des traductions ou à des compilations nous apparaît comme la marque des contrefaçons". [32] This seems to be a extremely weak argument for such a strong allegation. But of course it is not enough for Halbronn to disqualify the Significations as a contemporary fraud, in addition it has to be antedated. The reason for this is, because in it we find the oldest reference to the centuries, when Nostradamus speaks of the "interpretation de la seconde centurie de mes Propheties" [33] and Halbronn tries to save the thesis that no centurie was known at that time. What to make of a booklet on the effects of a lunar eclipse in 1559, distributed more than a decade after its occurrence? Who would ever buy this book and which publisher would be so foolish as to print such an obsolete work? It is as if a market analyst were to publish in 2003 a technical analysis of the probable development of the Dow Jones Index for the year 1991.

In all probability Nostradamus had in mind to publish a rejoinder to his critics, but he knew very well that such a book would be hard to sell. The public at large was not interested in fierce debates. Hence he decided to take advantage of the impending eclipse of the moon, to issue an interpretation of this prodigious sign in which he would also include a heated reply to his detractors. Most likely he wanted to bring the book out soon and did not want to lose time by writing a piece about the coming eclipse on his own. Therefore he relied on the work by Leovitius and had the brilliant idea of changing the subject from the interpretation of the celestial phenomenon without further notice on fol. Biir in the middle of a sentence and turn to the topic of the counter-attack - which was his central idea for this publication in the first place.

Halbronn also feels constrained to regard the fake 1563 Barbe Regnault almanac as yet another antedated edition, making part of the "Nostradamus scheme". There is one important necessity for him to place the true date of publication of this almanac in a later epoch, as the dedicatory letter contains not only allusions to the Excellent et Moult utile Opuscule and to the letter to César, but also to the Epître à Henri II. [34] In it the impostor writes that his prophetic powers are due to the "foureur" and a "naturel instinct". There is no mention of the "naturel instinct" in the Épître à César, but we encounter this term no less than three times in the dedicatory letter to Henry II introducing the last part of the centuries. Moreover there is no mention of the "naturel instinct" in the dedicatory letter of Nostradamus to Henry II in his Presages merveilleux pour lan 1557, which Halbronn thinks was used by later forgers to construct the Epître à Henri II as introducing the last three centuries. Hence there is an obvious need for Halbronn to regard this almanac as antedated. He maintains that it must have been published certainly after 1570. How does he reach this strange conclusion? The almanac carries on its frontispiece the quatrain C 3.34 of the Prophéties.

C 3.34

Quand le deffault du Soleil lors sera,

Sur le plain iour le monstre sera veu:

Tout autrement on l'interprétera,

Cherté n'a garde, nul n'y aura pourveu.Halbronn associates C 3.34 with C 2.45, as if it would become clear from this quatrain that the "monstre" mentioned is none other than l'androgyn which we encounter in C 2.45. He makes this connection because the shape of the androgyn of C 2.45.1 was interpreted by Chavigny in his booklet of 1570 [35] as a symbol of discord in France during the religious wars in the 1560s, and hence this association could not have been made before this time. But indeed there is nothing in C 3.34 that justifies such an interpretation. Nostradamus draws heavily on monsters in the Latin sense of prodigia, monstra, omina and portenta from the beginning of his production of almanacs and prognostications, in accord with the interpretation of such signs very much in vogue especially during the years 1552-1557, "l'age d'or des prodiges", as Céard puts it. [36]

The woodcut of the Siamese twins born in Paris on 21 July 1570

as represented in Jean de Chevigny's L'androgyn né è ParisNothing in C 3.34 supports the interpretation of a religious division, as a double-headed monster could probably do. Here Nostradamus only speaks of an eclipse of the sun and the fact that a monstrous creature will be seen in full daylight. There is also the possibility that monstre here is taken in the Latin sense of a "sign" and refers to the eclipse of the sun from the first line, with its sudden downfall of darkness in the middle of the day, as Brind'Amour indicates. [37] I tend to disagree with this explanation, because Nostradamus uses the term monstre in the centuries on many occasions, but almost exclusively in the sense of a monstrous creature. Nonetheless there is no indication of a specific monstrous creature that could point to Siamese twins, as was the case of l'androgyn, and as we encounter in C 8.68.3 and C 9.3.3, when Nostradamus speaks of "monstres double" and "monstres à testes double". I cannot see any reason, why this quatrain may not have been written in the 1550s or at any other time before that date, as it is an "innocent" prediction, common to the renaissance prophetic tradition of interpreting various prodigious signs.

Another argument of Halbronn in favor of the opinion that the 1563 Barbe Regnault almanac is antedated comes from the titlepage, where the printer is mentioned just as "Barbe Regnault" and not as "veuve Barbe Regnault" as she was called a year before on the titlepage of her Pronostication pour 1562. He explains: "La disparition de la mention "Veuve" est d'ailleurs une erreur des faussaires: du jour au lendemain une femme peut devenir veuve, elle ne peut cesser de l'être." [38] The last claim is certainly right, but the deduction that therefore it is likely that the work is a fake by a later hoaxer is not all that plausible as it may seem to him. Barbe Regnault had already published in 1558 the anti-nostradamian pamphlet Le Monstre d'Abus by Jean de La Daguenière. There we read on the frontispiece: "A Paris, pour Barbe Regnault". No mention of her widowhood. But at that time she was already a widow, her husband André Berthelin having died before October 1553! [39] On her almanac for the year 1561 again we find only "Pour Barbe Regnault". [40] Obviously at times she used to sign just as Barbe Regnault, at other times as "veuve Barbe Regnault".

Let us take a closer look at the publication dates of some counterfeit Nostradamus almanacs and prognostications. One publisher who produced at least three apocryphal almanacs for the years 1561, 1562, and 1563 was the afore-mentioned Barbe Regnault in the rue Saint Jacques "à l'enseigne de l'Eléphant" in Paris. Halbronn recognizes correctly that the epistle in the 1562 Pronostication of Nostradamus by Barbe Regnault contains elements that call to mind the letter to César. [41] It is interesting to have a closer look to this dedication to Jean de Vauzelles in the Pronostication nouvelle pour 1562 by Barbe Regnault. A dedicatory letter to the same Jean de Vauzelles was also printed in another Nostradamus prognostication for the same year at Lyon, the Pronostication nouvelle, Pour l'an mille cinq cents soixante deux by Antoine Volant & Pierre Brotot. Halbronn blames Chomarat and Benazra for not having seen the Barbe Regnault Prognostication pour 1562 and he declares about the text of the letter in the Volant & Brotot copy that Chomarat reproduces from secondary sources: "...l'Epître à Jean de Vauzelles, dont le texte qui appartiendrait à une édition lyonnaise est strictement identique à l'édition parisienne Veuve Barbe Regnault." This observation is not correct. The Barbe Regnault Prognostication nouvelle for 1562 does indeed contain the letter to Jean de Vauzelles, but it is far from being "strictement identique" to the version in the Volant & Brotot Pronostication.

A comparison of the letter published by Chomarat [42] with the Regnault Pronostication from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich (the same used by Halbronn), makes the fact clear. The most obvious difference is the lack of the citation of the quatrain in the Regnault Pronostication, which is all the more surprising, since this is the main reason for the dedicatory letter having been written in the first place. We read in the Volant & Brotot edition: [43] "...comme quand i en mis: Lors que un oeil en France regnera. Et quant le grain de Bloys son amy tuera, [... ] en infiny autres passages. Cela m'a causé une si grande amitié entre nous deux..." Whereas the Barbe Regnault version of the letter puts it: "...comme quand i'eu mis, Lors Cela m'a causé vne si grande amitié entre nous deux..." [44] The quote of the quatrain is completely suppressed in this version. There are some more differences between the two texts which lead to the conclusion that the Regnault version is a counterfeit edition based on the volume issued by Volant & Brotot. Possibly the pirate printers in the print-shop of Barbe Regnault composed from hearing, while someone read the text from the Volant & Brotot almanac out loud, and copied to hurriedly, by using the original Volant & Brotot version. By doing so maybe the reader jumped over some lines, so the quatrain got lost.

Fol. Aijv of the Pronostication nouvelle pour 1562 by Barbe Regnault

carries the mutilated letter to Jean de Vauzelles

Of special interest is the end of the dedicatory letter.

Volant & Brotot: "...cette mienne Pronostication, laquelle envoyee pour vous presenter par Brotot laquelle il vous plaira accepter d'aussi bon coeur que la vous presente. M. Michel Nostradamus. l'an 1561.

Faciebat M. Nostradamus Salonae petrae Provinciae xviij. Aprilis 1561, pro anno 1562."

Regnault: "...ceste mienne Pronostication, Laquelle enuoye pour vous presenter par Pierre Brotot.

Lentierement vostre frere & meilleur amy M. Michel Nostradamus Docteur en medecine de Salon de Craux en Prouence, l'an mil cinq cens soixante 2. Priant Dieu vous tenir en sa sainte grace, & moy en la vostre."

Here we encounter a mistake by the forgers who end the letter with the date 1562, whereas in the Volant & Brotot original it is correctly dated 1561. [45] Almanacs were supposed to be written and ready in the year before the one which they were aimed at. Obviously when Barbe Regnault got hold of the almanac of Volant & Brotot after it was published, she rushed to forge one of her own on the basis of this one early in 1562 and by mistake put this date under the letter to Vauzelles. Another error due to a rushed production without checking the content is the reproduction of the mention that her Pronostication would be presented to Vauzelle by Pierre Brotot! This was true of course for the original work by Antoine Volant & Pierre Brotot, but certainly not for the pirated edition of Barbe Regnault.

In any case we have another direct proof that at least the first batch of quatrains was known and published by 1560/1561. Jean de Vauzelles must have written to Nostradamus in 1560 or 1561 about his interpretation of C 3.55 as being a prediction of the death of Henry II. In addition, in the response of Nostradamus in his letter printed in toto in his Volant & Brotot Pronostication nouvelle for 1562, written before April 1561 (date of the faciebat), Nostradamus admits that he is the author of the quatrain in question.

Another detail pointing to the fact that fake and pirated almanacs were not antedated can be deduced from the fake almanac from Barbe Regnault for 1563. Besides quatrain C 3.34 on the frontispiece, all quatrains in the text come from the almanacs of 1555, 1557, and 1562. If it were a later antedated fake, the forgers might have also used quatrains from later works, but no, all were published prior to this date.

Of course there were abundant fake almanacs during Nostradamus's lifetime, put forth in his name. He himself attacks the forgers fiercely on several occasions, and the publishers authorized by Nostradamus do the same. [46] Especially in England we encounter a great number of fake almanacs of Nostradamus starting with the year 1559, and several printers were fined by the Company of Stationers for publishing such books. [47] Sir Thomas Challoner, the English ambassador in Spain, was sent a fake Spanish almanac of Nostradamus in November 1562 by his colleague Henry Cobham. [48] In France we have the evidence of Jean de Marcouville citing in a work written in 1563 and published in 1564 [49] a prediction of Nostradamus from his supposed almanac for 1563: "Aussi ilz ont escrit & pronostiqué, que c'est an present 1563 sera bien difficile à passer, pource qu'il sera plein de diversitez & adversitez: & un d'entre eulx a bien osé escrire qu'il y aura, non seulement mutation & changement de temps & d'estatz, mais aussi de religion." The note in the margin reads: "Nostradamus en la prediction de May." But his quote comes from the fake almanac of Barbe Regnault, where we read in the predictions of May: "...temps diuers & fort variable, plusieurs & diuerses mutations tant de temps que d'estats & de religion..." [50] Again here we have the direct irrefutable proof of a contemporary reader that the fake almanac of Barbe Regnault for 1563 was published and distributed at the latest in the very year 1563 and hence is certainly not an antedated edition.

It seems as if the turn of the late 1550s to the early 1560s must have been the start of the heyday of forged Nostradamus almanacs. Another piece of evidence comes from Hans Rosenberger's letter to Nostradamus from December 1561 in which he complains about the abundant production of counterfeit almanacs in his name. Nostradamus himself gets back to the incessant fabrication of fakes using his name in the "advertissement au lecteur" in his 1566 almanac, in which he explicitly cites the fake almanacs printed in several French cities, including Paris.

Evidence from an impostor: The discovery of a counterfeit almanac for the year 1565

Only very recently I was lucky to stumble across a hitherto unknown almanac for the year 1565 attributed to Nostradamus. Chomarat mentions this almanac in his bibliography referring to the information given by Philippe Renouard, who himself has not seen it, but cites the title from a "catalogue de vente". [51] Chomarat erroneously calls the printer of the almanac Thibault Berger. The printer is in reality Thibault Bessault. [52]

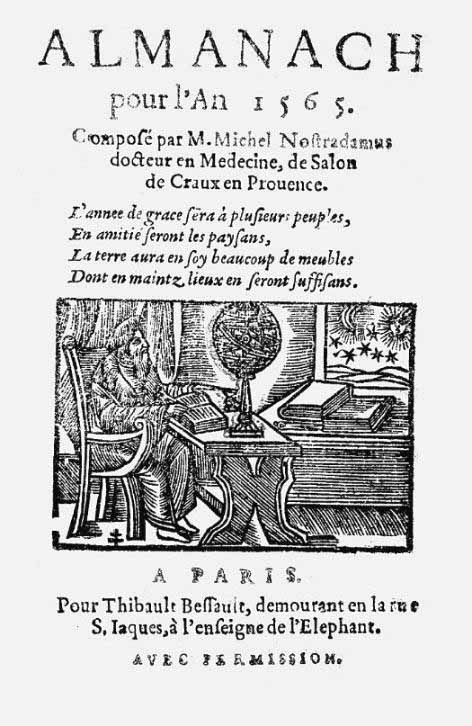

Frontispiece of the hitherto unknown Almanach Pour l'An 1565.

Composé par M. Michel Nostradamus by Thibault Bessault

I had the chance to examine the copy of this text of pseudo-Nostradamus prior to its being sold at auction and intend to give a detailed description of it in a separate publication. [53] What is interesting is the fact that Thibault Bessault was the son-in-law of Barbe Regnault and took over the press in the rue Saint Jacques "à l'enseigne de l'Eléphant" from her after 1563. He was active until 1565 and obviously carried on with the successful tradition of forged Nostradamus almanacs. In his almanac we find a quatrain on the frontispiece and quatrains for every month of the year. Some of these quatrains are ridiculously simple and easy to understand, not at all reflecting the characteristic style of Nostradamus. But some of them are indeed enigmatic and totally different in appearance from the others, and this not without reason. They are all rearrangements or simple copies of original quatrains from the Prophéties:

The quatrain for July in the Bessault 1565 almanac reads:

Loing vaguera par frenetique teste

Et delivrant un grand peuple d'impos,

Le penultiesme du surnom du Prophete

Prendra Diane pour seiour & repos.This is an obvious borrowing from C 2.28:

Le penultiesme du surnom du prophete

Prendra Diane pour son jour & repos:

Loing vaguera par frenetique teste,

Et delivrant un grand peuple d'impos.August (Bessault 1565):

Les exilez transportez dans les Isles

Qui de parler ne seront supportez

Seront conflictz, & mis deux à franchises

Pour le renom qui leur sera portezThis is an imitation of C 1.59:

Les exilés deportés dans les isles

Au changement d'ung plus cruel monarque

Seront meurtrys & mis deux des scintilles,

Qui de parler ne seront estés parques.September (Bessault 1565):

Le leopard au ciel estend son oeil,

Un aigle autour du soleil voit s'esbatre

Et par le monstre que sera le Soleil

Seront nombrez plusieurs gens pour combatreThis time the source is C 1.23:

Au mois troisiesme se levant le Soleil,

Sanglier, liepard au champ mars pour combatre:

Liepard laisse au ciel extend son oeil:

Un aigle autour du Soleil voyt s'esbatre.

The quatrain for November in the Bessault almanac is an exact copy of C 1.36 with the only exception that it has "à mort" in the fourth verse instead of "par mort". However of particular interest are the quatrains for October and December, because here the impostor copied from quatrains of the fifth and sixth centuries:

October (Bessault 1565):

Lors que Saturne sera hors de servage,

Leane sera par fleuves inundees

De sang troyen sera son mariage,

Et paix sera aux princes demandees.The copy comes from C 5.87:

L'an que Saturne sera hors de servage,

Au franc terroir sera d'eau inundé:

De sang Troyen sera son mariage,

Et sera seur d'Espaignols circundé.December (Bessault 1565):

Mars & le sceptre se trouvera conioinct,

Dessouz cancer calamiteuse guerre

Et peu apres le Roy aux princes ioinct,

Sera long temps pacifiant la terre.In this case C 6.24 was used for imitation:

Mars & le scepte se trouvera conioinct,

Dessoubs Cancer calamiteuse guerre:

Un peu apres sera nouveau Roy oingt,

Qui par long temps pacifiera la terre.

By comparison with the real Nostradamus almanac for 1565 published by Benoit Odo, the only known copy of which is kept in the Biblioteca Augusta del Comune di Perugia, it is clear that Thibault Bessault did not use the original for the year 1565 as source of his forgery like his mother-in-law did for her counterfeit production of the Pronostication for 1562, who relied on the original for the same year. Hence Thibault Bessault did not have to wait until the Benoit Odo almanac for 1565 was available. In comparison to the voluminous original of 163 pages, the Bessault almanac consists of only 32 folios, totally different in content. It is most likely, therefore, that the Bessault almanac was also composed and printed in 1564, to be ready before the year 1565.

Now we have a new terminus ad quem for the publication of centuries 5 and 6. The use of the two quatrains pertaining to the fifth and sixth centuries in the Bessault almanac shows that not only the first 300 and some quatrains were known by 1564, but also the fifth and the sixth centurie. This of course contradicts the reconstruction of the publication-history presented by Halbronn. It also contradicts the possibility that centuries 5 to 7 were the result of a creation by the League.

Let me add another observation concerning the peculiarities in the typesetting of some words in the Bessault almanac in respect to the du Rosne 1557 edition of the Prophéties. The word "penultime" (Bonhomme 1555, Anvers 1590) in C 2.28.1 is written "penultiesme" in the Bessault almanac like in the du Rosne 1557 edition. The line C 5.87.1 is usually given as "L'an que Saturne hors de servage," in all editions, except du Rosne 1557, where we read "L'an que Saturne sera hors de servage", [54] as in the almanac Bessault. These are certainly no proofs, but nonetheless indications that the source for the quatrains used in the counterfeit edition by Bessault or his anonymous author might have been the Prophéties of du Rosne 1557, which would mean that the du Rosne edition circulated during Nostradamus' lifetime, at the latest by 1564.

One interesting oddness concerns the woodcut on the frontispiece of the almanac Bessault. It is identical to the one used by Barbe Regnault on her fake Almanach pour l'An 1563. [55] This is no surprise, as the almanac Bessault issued from the same press. This woodcut was inspired by the one on the edition Macé Bonhomme 1555, which was also used by Antoine du Rosne in the issue of the Utrecht copy (6 September 1557). It seems that the printers at the "enseigne de l'Eléphant" in the rue Saint Jacques used the du Rosne 1557 edition as their source for the quatrains and the woodcut on the frontispiece. The woodcut in question is a very close copy. Its main distinguishing elements are the six stars in the window on the Regnault and Bessault titles as compared to the five stars at Bonhomme and du Rosne (Utrecht).

The belief in antedated fake almanacs and prognostications is certainly one of the weak points in Halbronn's demonstration. Besides the fact that nobody would buy an almanac for the year 1563 say in 1575, we have the proof of contemporary documents as presented above that these forged works were never antedated, but rather put out as quickly as possible. The idea of the falsifiers was to sell their pieces, and this would be impossible with an antedated almanac. Antedated almanacs would serve only the need of the theory of an historian like Halbronn. In reality they do not make any sense.

No doubt the owners of the press at the "enseigne de l'Eléphant" in Paris brought forth several generations of forgers. They had found a lucrative way of producing fake almanacs by exploiting nostradamian verse prophecies. After Barbe Regnault and Thibault Bessault the print shop was taken over by Antoine Houic, who ran the business until 1586. In 1569 and 1582 Houic published almanacs by a certain "Florent de Croz disciple de deffunct M. Michel de Nostradamus". [56] Hence several generations of printers at that place engaged in this activity and did so because it paid off. And no doubt their effort paid off only because they produced their almanacs at the right time.

Chavigny's Recueil and the Centuries

Let me add a brief note on yet another unusual remark of Halbronn concerning the manuscript of Jean-Aimé de Chavigny, Recueil des Présages Prosaïques. [57] He declares that in the Recueil we find no reference whatsoever to the centuries: "Or, force est de constater que le dit Recueil ne fait aucune référence aux centuries! Si celles-ci avaient été connues, à l'époque, il nous semble qu'elles n'auraient pas manqué de figurer parmi 'les oeuvres tant en oraison prose que tournée', au même titre que les quatrains des almanachs qui figurent, eux, bel et bien, au sein du Recueil des Présages Prosaïques, d'ailleurs assez mal nommé puisqu'il comporte des quatrains." [58] Nowhere in the Recueil does Chavigny state that his manuscript contains "les oeuvres tant en oraison prose que tournée". This is a citation from the introductory letter to his l'androgyn, in which he announced the plan to publish both the prose and verse prophecies of Nostradamus. The part with the verse prophecies found its way to the printers and was distributed as the Janus François, the work on the prose prophecies remained as a manuscript in the Recueil. It is obvious that Chavigny meant to produce a collection of excerpts only from the almanacs and prognostications and entitled it accordingly as covering the prophetic works of the author, the largest portions of which were in prose as opposed to the centuries, which were exclusively written in verse. The fact that a considerable number of the almanacs and prognostications also contained quatrains which of course were included by Chavigny in the Recueil, does certainly not mean that he should have included the quatrains from the centuries as well. Nonetheless it is certainly not the case that the Recueil "ne fait aucune référence aux centuries", as Halbronn argues.

It seems that Halbronn has not only not studied the Recueil, he has not even read Chevignard's book attentively enough. Otherwise he would have encountered a considerable number of clear references to the centuries. In the epistre liminaire for 1554 Nostradamus mentions the appearance of a strange event (Chavigny PP 98, 1554: "Devers nostre païs à la Durance adviendra un cas autant furieux & estrange, qu'on ait veu à vie d'homme. Ce sera à quatre ou cinq lieuës près d'Avignon, chose fort prodigieuse."), subsequently interpreted by Chavigny in his marginal note as being the prediction of the monster of Senas. His note reads: "Monstre né à Senas de Provence 1554. Voy la I. Centu[rie] quat[rain] 90." [59] At an extract for November 1559 (Chavigny PP 238, 1559) Chavigny notes: "Un Colonnel machine ambition, Cent[urie] IV, 62." [60] Unfortunately Bernard Chevignard has omitted the commentary of Chavigny to the quatrain for June 1555 (Chavigny PP 359, 1555), in which he makes yet another explicit reference to C 6.2 of the centuries: "Il remarque nos troubles de 1580 & plus outre. Sat[uren] estant en l'Urne 1580 & 81. C'est ce qu'il dit en ses Centu[ries] en l'an cinq cens octante plus & moins on trouvera le siecle bien estrange."

Again in his excerpts from the Significations de l'Eclipse Chavigny mentions the centuries: "De [vers] la plus foi[ble] par[tie], Entre les Pr[inces] le dernier honoré, Cent[urie] III [100]." [61] Chavigny associates a passage as reflecting the prediction of the siege of Geneva in the year 1589 in a marginal note to the présages en prose for 1561 with an allusion to the Prophéties (Chavigny: PP 204, 1561): "Il semble que cecy se rapporte au quat[rain] 37. de la 10. Cent[urie] ou il dit, grande assemblée pres du lac du Borget, se rallieront pres de Montmelian. Marchans plus outre pensifs feront proiet, Chamb[ery] Morai[ne] combat S. Iulian. Siege de Geneve 1589." Again in the extracts for the same year 1561 another note by our author reads: "Voy le qua[train] 47. de la I. Cent[urie] qui semble icy se raporter." (Chavigny PP 285, 1561).

The attentive reader will encounter implicit references to the centuries in the Recueil as well, in a marginal note to the extracts for the year 1558 (Chavigny PP 112, 1558) [62] : "Il dit ailleurs, Sa grande charge ne pourra soustenir, & Grand camp malade, & defait par embuches." The first part being a reference to C 6.13.4, which reads in the original "Sa grande charge ne pourra maintenir", the second to C 6.99.2. To December 1559 (PP 285) Chavigny notes: "Office changé en contraires qualitez. Du joug seront de. les 2 g. m." [63] This is a abbreviation of C 2.89.1 "Du jou seront demis les deux grands maistres". [64] A further implicit note to PP 380 (May 1559) [65] reads: "Exilez dans Rome. Tricast tiendra l'Annibalique ire." This is a quotation from C 3.93.3.

The assertion of Halbronn that there is no mention of the centuries in the Recueil is yet the more disturbing, as he explicitly makes reference to the marginal note of Chavigny concerning his publication of L'androgyn né à Paris as his argument for the date of termination of the Recueil. In this very note Chavigny draws our attention to a quatrain from the centuries: "Le né biparti c'est l'Androgyn à mon jugement, né à Paris 1570 duquel plusieurs ont escrit, & l'ont orné, J[ean] Daurat, Belleforest, & nous le representimes dans Lyon avec quelque description. Et l'Auteur mesmes en avoit parlé en ses centuries, Trop le ciel pleure Androgyn procreé [C 2.45.1]. Ce que s'accorde à ce qu'il veut dire icy: qu'après la naissance dudit monstre les pluyes cesseront."

Halbronn thinks that the Recueil dates indeed from 1570, when Chavigny had published his piece on l'androgyn under the name of Jean de Chevigny, and not from 1589 as mentioned on the first page by Chavigny himself. [66] If Halbronn were right in assuming the Recueil was ready by 1570, he would contradict his own reconstruction of the publication dates of the Prophéties, since we find in it, as I have shown, not only citation of quatrains from the centuries 1 to 4, 6, and 10, but also an explicit reference to the three bellicose "rois d'Aquilon" form the Epître à Henry II. In a marginal note Chavigny writes to the extracts of February 1559 (PP 47) [67] : "Ce Pentagermain est ce point le Pr[ince] Aquilonaire dont est parlé en l'Ep[istre] au Roy Hen[ry] sur les centuries."

I assume that Halbronn would now maintain that the marginal notes have been inserted at a later stage, but I am afraid there is no proof either for the assertion that the Recueil was finished by 1570, or that the marginal notes were written down at a much later time than the main body of the Recueil was. The topic of the Recueil shows once more the questionable methods applied by Halbronn, who turns the facts at his convenience to fit the hypothetical scheme of the supposed counterfeit production of the quatrains for the centuries by recourse to unsustainable arguments.

[1] Roger Prévost, Nostradamus. Le mythe et la réalité. Un historien au temps des astrologues. Paris, 1999. « Text

[2] This work was indeed composed already in 1555, as Coullard notes himself [fol. 100r]. « Text

[3] Prévost, op. cit., p. 245. « Text

[4] Antoine Couillard, Les Prophéties du Seigneur du Pavillon lez Lorriz. Paris, Antoine leClerc, 1556, fol. 8v. « Text

[5] The numbering follows the critical edition of Pierre Brind'Amour, Nostradamus. Les premières centuries ou Propheties (édition Macé Bonhomme de 1555). Genève, 1996. « Text

[6] Laurens Videl, Declaration des abus ignorances et seditions de Michel Nostradamus, de Salon de Craux en Provence ovre tresutile & profitable â un chacun. Avignon, Pierre Roux and Ian Tramblay, 1558, fol. D4r. « Text

[7] Videl, op. cit., fol. D4r. « Text

[8] Videl, op. cit., fol. D4v. « Text

[9] Videl, op. cit., fol. E1r. « Text

[10] Robert Benazra, Les premiers garants de la publication des Centuries de Nostradamus ou la Lettre à César reconstituée. http://ramkat.free.fr. Analyse 34. « Text

[11] Benazra, Les premiers garants, op. cit. « Text

[12] Cf. Elmar R. Gruber, A Rejoinder to Halbronn. http://ramkat.free.fr. Analyse 25. « Text

[13] Jacques Halbronn, Documents inexploités sur le phénomène Nostradamus. Feyzin, 2002, p. 97-98. « Text

[14] Cf. George Minois, Histoire de l'avenir. Paris, 1996. « Text

[15] Cf. Elmar R. Gruber, Nostradamus - Sein Leben, sein Werk und die wahre Bedeutung seiner Prophezeiungen, Bern, 2003, pp. 87-122. (Nostradamus: His Life, his Work, and the True Meaning of his Prophecies). « Text

[16] Jacques Halbronn, Les Prophéties et la Ligue. In: Prophètes et prophéties. Cahiers V. L. Saulnier 15. Paris, 1998, p. 95-133. « Text

[17] I adopt the style of citation of the centuries formulated by Brind'Amour (Nostradamus. Les premières, op. cit.), which provides the clearest rendering: C (centurie), followed by number of the centurie, followed by number of the quatrain, followed by (if indicated) number of the verse. « Text

[18] Cf. Gruber, Nostradamus, op. cit., pp. 12, 129. « Text

[19] Patrice Guinard, Nouvelle réponse aux allégations de Jacques Halbronn. Nostradamus : La controverse Halbronn, Guinard, et ceteri http://cura.free.fr/22contro.html. « Text

[20] Jean-Aimé de Chavigny, La premiere face du Ianus François, contenant sommairement les troubles, guerres civiles & autres choses memorables advenuës en la France & ailleurs dés l'an de salut M.D.XXXIIII. iusques à l'an M.D.LXXXIX ... Lyon, heritiers Pierre Roussin, 1594, p. 254. « Text

[21] Walter Schellenberg, Memoiren. Köln, 1959, p. 301. « Text

[22] Louis De Wohl, Sterne, Krieg und Frieden. Astrologische Erfahrungen und praktische Anleitung. Olten, 1951 (The Stars of War and Peace. 1952.) « Text

[23] Halbronn, Les Prophéties et la Ligue, op. cit., p. 122. « Text

[24] Patrice Guinard: Avertissement aux thèses de Jacques Halbronn. Nostradamus : La controverse Halbronn, Guinard, et ceteri http://cura.free.fr/22contro.html. « Text

[25] Halbronn, Documents inexploités, op. cit., pp. 182-184. « Text

[26] Jacques Halbronn, Jean Dorat et la "miliade" de quatrains (en réponse aux documents signalés par Patrice Guinard). Nostradamus : La controverse Halbronn, Guinard, et ceteri http://cura.free.fr/22contro.html. « Text

[27] Halbronn, Documents inexploités, op. cit., p. 178 « Text

[28] Halbronn, La célébration du cinquième centenaire de la naissance de Michel de Nostredame. http://ramkat.free.fr/ Analyse 19. « Text

[29] fol. Biiv. « Text

[30] Cf. Gruber, Nostradamus, op. cit., pp. 71-72. « Text

[31] Cyprianus Leovitius, Eclipsium omnium ab anno Domini 1554 usque in annum Domini 1606 accurate descriptio et pictura... Augsburg, Philippus Ulhardus, 1556. « Text

[32] Halbronn, La célébration, op. cit. « Text

[33] fol. Biir. « Text

[34] Cf. Pierre Brind'Amour, Nostradamus astrophile. Les astres et l'astrologie dans la vie er l'ouvre de Nostradamus. Paris, 1993, p. 488. « Text

[35] Jean de Chevigny, L'Androgyn né a Paris, le XXI. Ivllet. M. D. LXX. Lyon, Michel Iove, 1570. « Text

[36] Jean Céard, La nature et les prodiges. L'insolite au XVP siècle en France. Genève, 1996, p. 161. « Text

[37] Brind'Amour, Nostradamus, Les premières Centuries, op. cit., p. 380-381. « Text

[38] Jacques Halbronn, Réflexions sur les méthodes de travail des nostradamologues. http://cura.free.fr/22contro.html (2002). « Text

[39] Cf. Philippe Renouard, Imprimeurs et libraires parisiens du XVIe siècle. Ouvrage publié d'après les manuscrits de Philippe Renouard par le service des Travaux historiques de la Ville de Paris avec le concours de la Bibliothèque nationale, t. III, Paris, 1979, p. 279-281. « Text

[40] Daniel Ruzo, Le testament de Nostradamus. Monaco, 1982, p. 261. « Text

[41] Halbronn, Réflexions sur les méthodes, op. cit. « Text

[42] Michel Chomarat, Bibliographie Nostradamus, XVIe-XVIIIe siècles (with Jean-Paul Laroche). Baden-Baden, 1989, no. 49. « Text

[43] Chomarat, op. cit, p. 36-37 has published the letter which is printed on fol 22v of the Prognostication nouvelle. « Text

[44] fol. Aijv. « Text

[45] The forgers did not recognize their own mistake, as on the preceding fol. Aijr they printed: "Faciat M. Nostradamus Salone Petre Provincia de mese Aprili 1561. pro anno 1562." « Text

[46] Cf. e.g. the "Extrait du privillege (sic) du Roy" in the Almanach Pour l'An 1557 Aiv-Aiir, in which only the almanacs published and "paraphez" by Jacques Kerver and Jean Brotot were approved. « Text

[47] Eustace F. Bosanquet, English Printed Almanacs and Prognostications. A Biographical History to the Year 1600. London, 1917, p. 35, pp. 194-195. « Text

[48] Cf. Joseph Stevenson (ed.), Calendar of State Papers, Foreign Series, of the Reign of Elizabeth, 1562. London, 1867, p. 445. « Text

[49] Recueil memorable d'aucuns cas merueilleux aduenuz de nos ans... Paris, 1564, fol. 9r. « Text

[50] fol. Cviir. « Text

[51] Chomarat, op. cit. no. 65, p. 45. Renouard, op. cit., t. III, p. 297-298. Robert Benazra, Les Pronostications et Almanachs de Michel Nostradamus. http://cura.free.fr/docum/20benaz2.html. « Text

[52] Almanach Pour l'An 1565. Composé par M. Michel Nostradamus Docteur en Medecin, de Salon de Craux en Provence. A Paris Pour Thibault Bessault, demourant en la rue S. Iaques, à l'enseigne de l'Elephant. Avec permission. « Text

[53] At an auction of old and rare books at Zisska & Kistner, Munich, Germany, 2001. « Text

[54] This is the rendering in the Budapest copy. The Utrecht copy has "L'an que Saturne sera hors de servaige". « Text

[55] Woodcut A2 in the iconography of Robert Benazra, Répertoire chronologique nostradamique (1545-1989). Paris, 1990, p. 636. Chomarat, op. cit. p. 39, fig. 11, Benazra, op. cit., p. 59. « Text

[56] Benazra, op. cit., pp. 91, 115; Chomarat, op. cit., nos. 110, 137. « Text

[57] Cf. Bernard Chevignard, Présages de Nostradamus. Présages en vers 1555-1567, présages en prose (1550-1559). Paris, 1999. « Text

[58] Halbronn, Jean Dorat et la "miliade", op. cit. « Text

[59] Chevignard, op. cit., p. 204. « Text

[60] Chevignard, op. cit., p. 353. « Text

[61] Chevignard, op. cit., p. 378. « Text

[62] Chevignard, op. cit., p. 300. « Text

[63] Chevignard, op. cit., p. 358. « Text

[64] Chavigny comes back to this quatrain in his Janus François, interpreting the two grand masters as the Duc de Guise and the Duc de Mayenne (Chavigny, Janus François, op. cit., p. 268). The version "du jou" can only be found in the Bonhomme 1555 edition. All other editions carry "un jour" or "du jour". Cf. Brind'Amour, Nostradamus, Les premières Centuries, op. cit., p. 321. « Text

[65] Chevignard, op. cit., p. 369. « Text

[66] Halbronn, Documents inexploités, op. cit., pp. 133-135. « Text

[67] Chevignard, op. cit., p. 332. « Text

|

http://cura.free.fr/xxx/26grub1.html ----------------------- All rights reserved © 2003 Elmar R. Gruber |

|

|

|

|